Planning for Spring 2026: Getting the Most from Your Seed Choices

While autumn drilling often takes centre stage, spring cropping remains a vital part of rotations across the UK. Whether it’s barley, oats, wheat, pulses, or oilseeds, spring-sown crops deliver flexibility, risk management, and opportunities to improve soil health and business resilience.

As we look toward spring 2026, now is the time to review your seed requirements and think strategically about how your crop choices can best support your wider farm objectives and end markets.

The Value of Spring Cropping

Spring crops continue to earn their place in rotations for several reasons:

Market flexibility – From malting barley and quality wheats to peas and linseed, spring crops open up valuable market and cashflow opportunities.

Weed management – A well-timed stale seedbed and spring drilling can dramatically reduce blackgrass and other problem grassweeds.

Workload balance – Spreading cultivations and drilling between seasons helps relieve pressure on busy autumn schedules.

Soil improvement – Overwintered land benefits from rest, drainage, and organic matter additions before lighter spring cultivations.

Nutrient management – Legumes such as peas and beans naturally fix nitrogen, reducing inputs and improving soil condition for following crops.

Building a Balanced Spring Plan

Spring drilling decisions are often influenced by soil conditions and weather windows, so flexibility is key. Good seedbed preparation, careful variety choice, and attention to seed treatments can all make a significant difference to establishment and final yield.

Spring cropping isn’t just about filling gaps — it’s a strategic opportunity to support the rotation. Each crop brings different benefits, so it’s worth thinking about where they fit best in your system.

Spring cereals remain the backbone of spring drilling. Barley continues to dominate, offering excellent end-market opportunities for both malting and feed, as well as reliable agronomics and competitive yields. Spring wheat is another strong option, particularly after roots helping maintain cereal area and rotational structure. Oats are also offering consistent performance and strong market interest. They are considered a low-input cereal that helps break disease cycles, especially in a second cereal slot, and their strong root systems help to improve soil structure.

Pulses, including peas and beans, are popular for both environmental and commercial reasons. Their nitrogen-fixing ability supports soil health and helps reduce input costs for following crops, while market demand for quality UK-grown pulses remains robust.

Linseed continues to prove its value as a versatile break crop. Its benefits for weed management and rotation diversity, make it an increasingly practical option for many farms.

Looking Ahead

Spring crops continue to underpin resilient, profitable, and sustainable arable systems. Reviewing your 2026 plan now ensures you secure preferred varieties and market opportunities well ahead of drilling.

We offer a comprehensive portfolio of spring seed options alongside advice to help you choose the right fit for your rotation and commercial goals.

Selecting the Right Maize Variety

With November now here, attention is turning to maize – a highly versatile crop that serves a variety of purposes, from forage and anaerobic digestion to grain production. Maize is particularly valued in the biogas sector for its high dry matter yield and excellent energy content. In the livestock industry, it’s equally prized for its nutritional profile, providing high energy and starch levels that support both fattening livestock and boosting milk production. Maize offers a wealth of benefits. It delivers strong yield potential and can thrive across a wide range of climates, thanks to the many varieties available.

Choosing the right maize variety is essential. What is the end use? Grain, forage, or biogas. Then consider your location and soil type, as warmer areas and lighter soils suit different varieties. Finally, plan for harvest timing, since later-maturing types on heavy soils can pose challenges if conditions turn wet.

Speak to your ADM Farm Trader today to find out more about our maize portfolio.

Premium Barley Contracts

We’re pleased to offer a range of competitive buyback contracts for malting barley growers, designed to support growers in a market where demand remains challenging.

Our recently launched min–max premiums over futures for both domestic and export markets provide clear visibility on pricing and the freedom to secure value when opportunities arise, giving reassurance on while leaving plenty of scope to capture upside.

Our fund model brings an innovative, algorithm-driven marketing approach, paired with the added advantages of both area and quality flexibility.

Carbon Border Tax: What It Means for UK Fertiliser Prices

The UK farmer is now facing a new carbon border tax on fertiliser imports in the coming years. The UK’s version of the EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) will start in January 2027. Imported fertilisers such as ammonia, urea and DAP will incur charges reflecting their carbon emissions, much like a tariff on the CO₂ emitted to make them. The goal of CBAM is to stem non-EU carbon leakage by imposing on imports the same carbon cost borne by domestic producers.

The UK however is not blessed with large fertiliser production capacity. After its main ammonia production facilities closed in 2023, the UK must rely on imports many of which coming from outside of the EU meaning this carbon cost will more directly influence UK landed fertiliser prices. Domestic nitrogen production is limited, so UK farms have fewer buffers to absorb the shift.

Short Term 2026: Early Ripples in Fertiliser Costs

In 2026 the EU mechanism begins a year ahead of the UK. Projections suggest nitrogen fertiliser prices will rise ammonia could cost 10-20% more in 2026, urea slightly behind, and DAP around 2-5% up from the baseline. The UK will not yet collect the levy, but it may feel indirect pressure if global suppliers and trade flows shift from the EU market and tighten elsewhere.

However, market commentary points out that many EU importers still one and a half months out remain uncertain about how CBAM costs will be calculated: benchmarks, emission scopes and administrative charges remain unclear. A November 2025 report by S&P Global Commodity Insights stated, “Fertiliser importers face significant calculation uncertainties, meaning the cost impact is still not fully defined.”

Medium Term (by 2030): Steeper Prices as Carbon Costs Climb

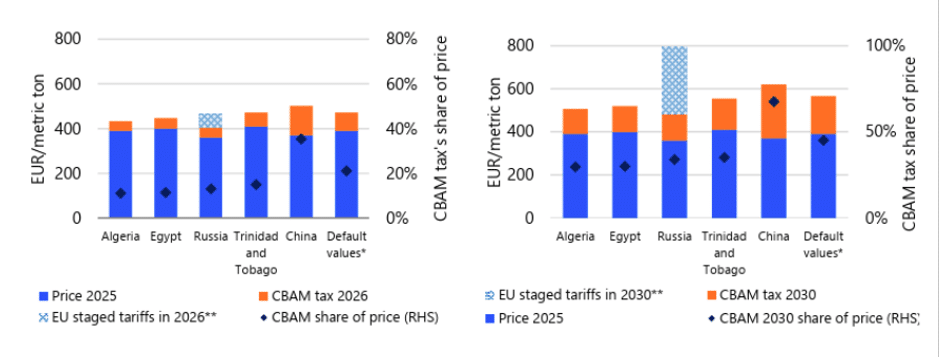

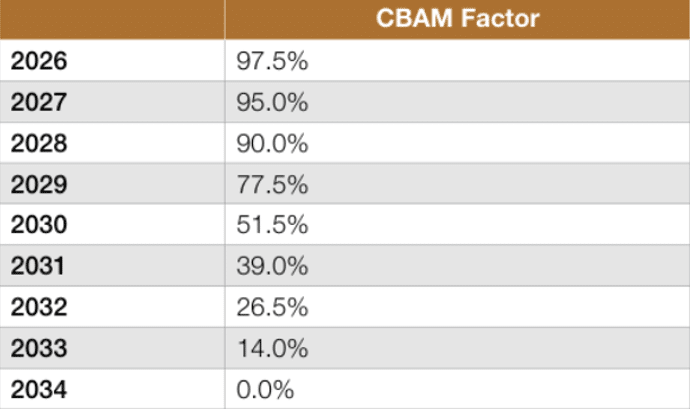

From 2026 to 2034 the EU gradually removes free allowances using the CBAM factor. This factor starts at 97.5 per cent in 2026 and falls stepwise to zero in 2034, so each year a larger share of embedded emissions becomes chargeable.

Rabobank estimates that, once the system has bedded in, carbon costs alone could make imported ammonia up to 50 per cent more expensive by 2030, urea about 45 per cent more, and DAP around 10 per cent more versus 2025 levels. If we map these increases onto the CBAM factor path, an illustrative price profile emerges.

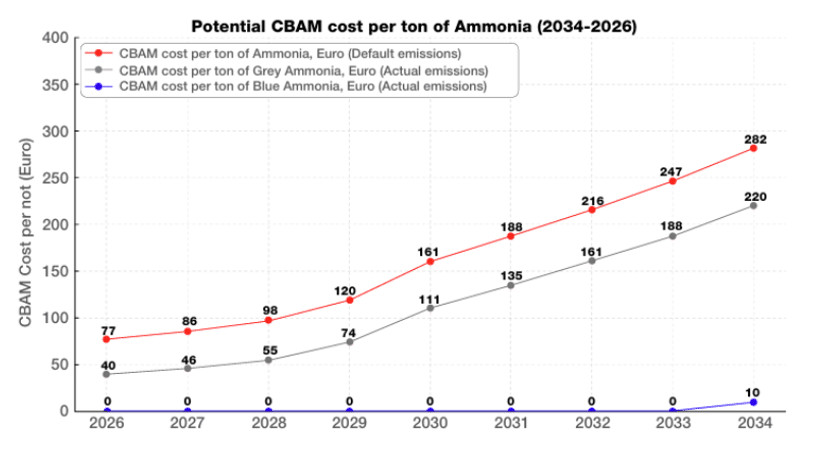

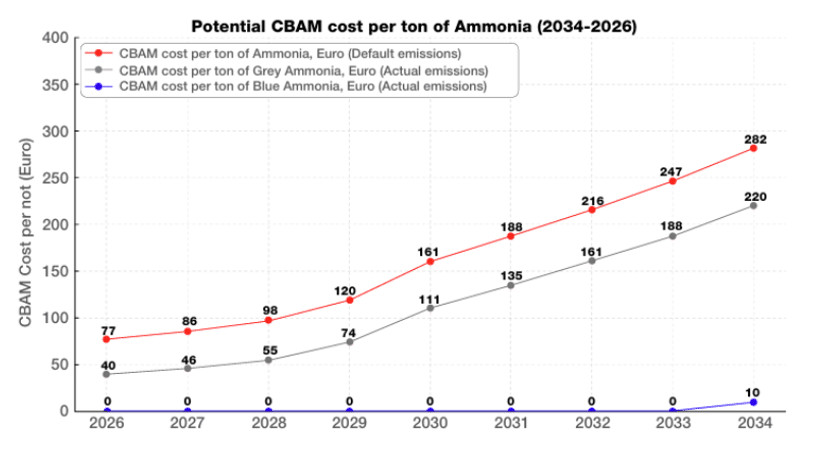

Assuming a 2025 import price of 400 euro per tonne for ammonia, the carbon element might add roughly 40–60 euro per tonne in 2026, rising towards 80–100 euro by 2030 as the factor drops from 97.5 to 51.5 per cent. For urea, a 350 euro base could see a carbon add on of around 30–50 euro by 2030, while DAP at 500 euro may carry an extra 20–25 euro. These numbers are indicative and depend heavily on the future EU and UK carbon price, but they show how the falling CBAM factor gradually pushes more cost into the fertiliser line.

The UK regime, due in 2027, is designed to track the domestic carbon price in a similar way, with the explicit aim of preventing carbon leakage into the UK market. If London chose to mirror the EU factor schedule, UK import prices for ammonia, urea and DAP would follow a similar rising path, albeit scaled to the UK carbon price rather than the EU one.

Producers with high emission intensity, for example coal based plants in China or Trinidad and Tobago, would see the largest increases; lower emission producers in the United States, North Africa and the Gulf become more competitive on a landed basis. Domestic EU producers of AN, ammonia and urea gain a relative advantage. European capacity is not sufficient to replace all imported nitrogen, so imports remain essential and prices stay linked to global supply.

Urea price including CBAM tax by origin. 2030 estimate

Urea price including CBAM tax by origin. 2026 estimate

Rabobank, 2025

Long Term (post 2030): A New Normal Arrives

After 2030 the fertiliser market enters a new era. By 2034 free allowances drop away altogether and the full embedded emissions of imports are exposed to the carbon price. At the same time, low carbon options gain traction. Blue ammonia projects in the United States and Middle East are forecast to reach cost parity with conventional ammonia around 2030, with green ammonia further out as technology and policy support mature.

Table showing the drop away of EU Free allowances. Expected to be mirrored by the UK.

In this environment UK farmers can expect straight nitrogen fertilisers to carry the largest and most volatile carbon premium, with NP, NPK and NS products seeing smaller but still noticeable rises. The exact bill per tonne remains uncertain, but the direction of travel is clear: fertiliser prices will increasingly reflect not only the gas, oil and agricultural markets but the carbon market as well.

Conservative modelling of CBAM cost per tonne on Ammonia Prices. Reflecting EU ETS Carbon price of 60 – 100 Euro / T CO2.

PWC, 2025

Aggressive modelling of CBAM cost per tonne on Ammonia Prices. Reflecting EU ETS Carbon price of 90 – 180 Euro / T CO2.

PWC, 2025